Akshayuk Pass

The Akshayuk Pass traverse spans almost 100 kilometres of breathtaking Arctic scenery on Baffin Island, Nunavut. It follows a traditional Inuit route between the communities of Pangnirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq, through a glacier-carved valley in the shadow of massive granite walls. Mount Thor, the world’s largest vertical drop, rises 1200m above the valley. Another highlight was Mount Asgard, two 1000m granite pillars, as seen in the James Bond movie “The Spy Who Loved Me”. Hundreds of metres above the valley, hanging glaciers - the edges of the mighty Penny Ice Cap - give way to moraines and fast-flowing creeks.

The remoteness of this area cannot be understated. The nearest rescue helicopter is often thousands of kilometres away in Jasper, Alberta. Hazards include extreme weather, river crossings, quicksand, high winds, rockfalls, and polar bears. All hikers must register with Parks Canada, providing details such as detailed schedules and “a list of your large identifiable equipment” to assist with rescue operations if needed. At the same time, it's relatively accessible for somewhere so remote, with a mostly well-defined route and established tourist infrastructure at either end of the pass.

I hiked this route, along with my dad, his friends Dave and Neil, and Dave’s son Eli, in August 2024. It was the most awe inspiring hike I've done. August was the ideal time for this trip, with the snow melted from the valley floor and relatively low water levels in the creeks. See the end of this post for some logistical tips.

The adventure begins

All flights to Pangirtung and Qikiqtarjuaq pass through Iqaluit, Nunavut’s capital, and almost all flights to Iqaluit pass through Ottawa. Thanks to some rescheduling, my layover in Ottawa was only 36 minutes long. Somehow I made my connecting flight on time, and soon I was on my way north. Over the next three hours, the trees on the ground gave way to barren lands, then ocean.

It was a balmy 5 degrees in Iqaluit. I dropped luggage off at my hotel, got a nice shawarma dinner - the only meal in town under $30 - then spent the afternoon walking around town. At 7,429 people, it is by far the smallest capital city in Canada, and has an end-of-the-world feel. Houses are built on stilts to avoid permafrost melting.

In the evening I hiked along the Apex Trail, a 5km walk along the coast to the community of Apex. Polar bears have been seen outside the town on rare occasions and I was conscious of the fact that my jacket still smelled like a Lebanese restaurant.

The next day, I walked back to the airport to catch my flight to Pangnirtung, located to the northeast of Iqaluit across Cumberland Sound. As the plane descended towards town I caught my first glimpse of the Baffin Mountains: sheer walls of ice-capped granite rising in the distance. To land, the pilot had to perform a 180 degree turn and dive between the walls of the fjord, while negotiating crazy turbulence. The plane bounced from side to side in a way that really reminded me of how small the aircraft was, and how far we were above the fjord. The locals were completely unfazed.

I checked in at Markus’s B&B (one of two accommodation options in Pang) then walked around town, which consists of two halves separated by the airport. The Hudson’s Bay Company blubber station and the views of the fjord were highlights. Dad and I met at Pangnirtung’s finest (and only) restaurant, a KFC located inside the Northern Store. We ordered takeout and ate lunch at the old Hudson’s Bay Company blubber station. This is easily the second strangest place at which I’ve eaten KFC.

In the afternoon Dad and I hiked to Mt. Duval and Alaniuja Peak, two mountains above Pangnirtung, described in a separate report.

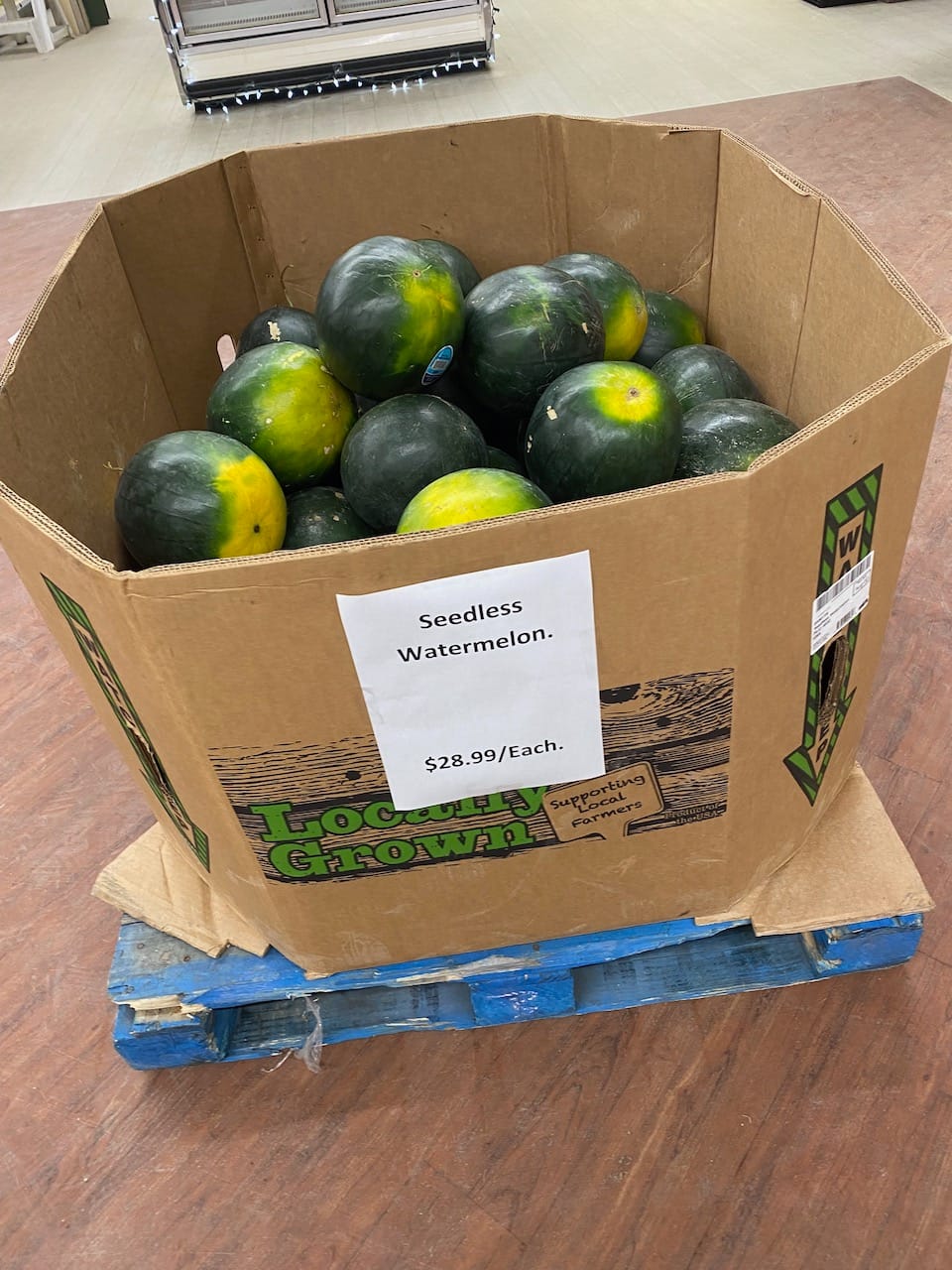

I spent the next day in town, walking around the area and enjoying another KFC lunch. Due to the fuel situation, I stocked up on cold meals at the Northern Store. Essentials (some fruits, meats, cheese) are heavily subsidized to Ontario prices and weren’t as expensive as expected, but the cost of everything else reflects the long journey needed to get there. The day’s special: a large crate of watermelons, on sale at $28.99 each.

Neil, Dave, and Eli arrived on the afternoon flight, and we all met at the docks. The first journey: a 30-minute boat ride from Pangnirtung to the southern trailhead at Overlord. The boatman, Peter Kilabuk, was the MLA for Pangirtung in the early 2000s and the speaker of the Nunavut legislative assembly. We traveled up the fjord past taller and steeper mountains shrouded in clouds and embraced by waterfalls. The tide was quite low, and we landed a few kilometres south of the official trailhead.

The traverse

We found ourselves on a beach surrounded by massive granite cliffs as far as the eye could see. Glaciers had carved near-vertical edges out of the mountains. To the north was the estuary of the Owl River. This was the most desolate landscape I had ever seen. No plants were visible, aside from small tufts of grass and Arctic willow. Further away, the river curved around a corner and disappeared from view.

The five of us headed north along the west side of the fjord, getting used to our heavy packs. We soon reached the “official” Overlord West trailhead at kilometre 98, marked by a cairn and a Nunavut flag. It was 9:30pm, but it was still bright and sunny out.

There is a distinct trail for most of the hike, but there are long stretches where hikers are either walking through bogs, tussocks (spongy mounds of grass - more on this later), or along the beach. We kept hiking for another 3.5km, then negotiated the first of many bogs to reach the Ulu shelter. There are several emergency shelters along the pass, with nearby outhouses. They’re painted bright orange and are easy to spot from far away. Camping is not permitted inside the shelters, but the areas near them make good campsites.

At the shelter, we met two hikers from Iqaluit and Alberta who gave us lots of helpful information about the trail. In particular, they warned us about the river crossing at the outflow of the Highway Glacier. We had dinner around 11pm, set up camp, and finally fell asleep around midnight. It was still bright outside.

The next day we woke up to thick fog everywhere, but it cleared off quickly to reveal even more stunning views. We continued along the west bank of the Owl River, mostly walking on sand.

At one point we met a large guided group and had a short chat with the guide. These guys had been on the trail for 15 days and still had a couple more to go! The guide was surprised that we were doing this unguided, complaining about the dangers of the route, especially something called the “moraine of pain” (we’re not sure which one this was) and warning us that “there’s no way” we’d make it to the Thor shelter, 16km away, that day (we reached the shelter pretty quickly that day, with little difficulty). We wished them luck and moved on.

A lot of the next few kilometres were spent on the banks of the river, where solid river sediment was the most durable surface, except when it wasn’t… Most of the surface was solid, but every hour or so we’d reach a section of quicksand and sink into the sand. We got in the habit of testing the sand with our hiking poles to keep safe, which allowed us to avoid most - but not all - quicksand.

Every step revealed new scenic vistas, each mountain taller and more jagged than the last.

Around kilometre 88, we ascended the first of many terminal moraines, ice-cored ridges of gravel left behind by retreating glaciers. These moraines were usually around 100 metres high and presented the only significant elevation gain of the trip. We looked from the moraines to the now much-diminished glaciers that spawned them and contemplated the changes that have occurred here.

We followed footsteps up the side of the moraine and walked along its crest for a while, bypassing Crater Lake. The extra height gave us a good vantage point of the valley and the braiding of the wide Owl River. We caught our first glimpse of the vertical drop of Mount Thor, far away.

Eventually we made our way down the moraine. In a few kilometres we crossed the Arctic Circle, marked by a sign. In the distance, Mount Thor was framed by the valley walls. It felt like we’d crossed a milestone. Interestingly, there is another broken Arctic Circle marker a few hundred metres north.

Just past the Arctic Circle we reached Schwartzenbach Falls. At 520 metres high, this is the fourth tallest waterfall in Canada and the tallest outside BC.

A few kilometres later, we negotiated another moraine and reached the valley floor. A loud cracking sound rang out above us as a massive cloud of rocks tumbled down the cliff face. The cloud, easily the size of several houses, seemed to fall in slow-motion. We were far away from its path but we did not linger long. A very powerful reminder of the geologic forces constantly shaping this place.

Over the next couple of hours, we continued toward the Thor shelter. The sheer face of Mt. Thor loomed larger as we approached.

A few kilometres from the shelter, we came across two climbers outside their tent. They had been at their base camp for almost two months and had already summited nearly every peak in the area! Their attempt on Thor was planned for the following day. We didn’t catch their names, but they were likely well-known in the climbing world. After wishing them luck, we carried on and set up camp near the Thor shelter.

The next day, our first obstacle was Half Hour Creek. This creek is notorious for high water levels, with one group recording a 4 day wait at that creek in the logbook. We were luckier, and were able to cross the creek right away.

As we headed north, Mount Thor still dominated the valley behind us, somehow getting even more vertical and sheer from this angle. Several more moraines gave us a bird’s eye view of the valley, with Thor looming in the background. It was soon joined by crown-shaped Breidablik Peak.

We walked around the shore of Summit Lake, dodging quicksand on the beach. There was a small ice cave at one point. Our original goal was Turner Creek, but we ended up camping on the moraine a couple kilometres before that.

The next day involved the most intense creek crossings: Turner Creek, the Norman River, the outflow of the Highway Glacier, and the Owl River, each one deeper and faster than the last.

We crossed knee-deep Turner Creek early in the morning, climbed another moraine, then reached a sandy peninsula with a large dune and many beautiful blue ponds. Here we met the only other group we’d see for the rest of the trip, a French couple with some good advice about the route ahead.

After some more ups and downs along the moraines, we faced a long descent to the Norman River, which was also knee-deep with several braids.

Past the river, the route headed southwest along the lakeshore. The moraine here got steeper and steeper and we found ourselves boulder-hopping along the water’s edge to avoid rockfall.

Eventually we reached a rocky valley, an outlet of Glacier Lake which dried out in the 1950s. Below the rocks flowed the waters of the Owl River. As we rested, the clouds cleared, and we finally saw Mount Asgard to the west.

Around the corner were the most dangerous river crossings of the trip. The Chrismar map describes the Rundle River crossing as “extremely dangerous”, so we avoided it by staying on the north bank of the Owl River. This forced us to cross the outflow of the Highway Glacier, which we’d been warned about. This was a fast-flowing river almost waist-deep in places. We stumbled across, holding on to our poles for stability.

This was only half the battle. We were still on the wrong side of the braided Owl River, over a kilometre wide. Our destination, the Glacier Lake shelter, was a tiny orange dot on the other side of the river. We slogged across several braids, some up to waist-deep, through the massive river floodplain. At times we had to cross in a diagonal formation to provide shelter from the current. At each crossing, the glacial water and bitter winds chilled us to the bone. Eventually we reached dry land at the Glacier Lake shelter, resting under the evening sun to dry off and warm up. The sun felt so good!

At 9:30pm, the night was still young, so we walked for five more kilometres, negotiating boggy terrain, then camped by the river.

The next day, we woke up to fierce winds collapsing our tents. The area is known for these sorts of gales, but so far we’d mostly avoided them. It was difficult to stand upright, and wind blew sand everywhere. At one point I almost lost my jacket and had to sprint after it. Luckily, things calmed down after a few hours. We continued up the valley past many mini-Thors, looking back at Mount Asgard until it, too, disappeared behind a corner.

There is no visible trail for most of the northern half of the traverse. The terrain underfoot was about 60% walkable sand and 40% bog or tussock. We tried to stay on the riverside as much as possible. Sometimes, we would walk along what seemed like a long sandy stretch, only to get cut off by rejoining streams. We also had to negotiate many streams flowing into the Owl River, almost all of which were easily walkable, but some required long jumps or pole vaults.

We had lunch at the June Valley shelter. Like all shelters, it had its own logbook, with signatures and musings from various parties throughout the years. One group had drawn a beautiful picture of the shelter and nearby monoliths. Unfortunately, the picture was on page 69 and had been vandalized accordingly.

On we continued, past many nameless peaks. To quote the map, “Feature names are uncommon in this part of the Pass, a testament to its relative isolation and as a deliberate contrast to the busy naming period of the 1950s/60s for the southern part”. Some of these nameless peaks seemed like they could be ascended via scrambling.

As I jumped across one small creek, the water below me erupted in a frenzy of splashes! Something large was underwater. I landed on the other side quickly, with all digits intact. Through the sand, we saw several spawning Arctic char. Terrifying.

We camped at the Owl River shelter in the shadow of another vertical rock face.

The next day, we faced our second-last major creek crossing. After some attempts to find a route that would allow us to stay dry, we gave up and walked through the water at the shallowest point. The next few kilometres were spent slogging through boggy tussocks near the base of the mountains.

We came to a small rise in the terrain and I saw something I’ll never forget. In the distance was the North Pangnirtung Fjord. On the beach were five to ten icebergs, small specks in the horizon but actually the size of a building. They grew larger as we approached the beach. After one last creek crossing, we were on the beach 5km away from our pickup spot at the last shelter.

Polar bears are found around beaches, so we did not want to linger. We continued along the beach, underneath massive granite cliffs, and eventually saw the shelter behind a boulder.

We’d arranged a pickup with Billy Arnaquq, the boat operator at Qiqiktarjuaq. We were several hours ahead of schedule, so we sent him a message and relaxed in the shelter for a few hours, admiring the scenery. I might have set a record for the northernmost latitude at which Brooklyn Nine-Nine has been watched. Later, we were joined by Sebastien, an Inuk from Quebec who had recently moved to Qikiqtarjuaq. He’d worked and travelled all around the country, including the two other territories, before moving to Qik for the first time a couple years earlier. He had some interesting stories.

Billy arrived 30 minutes early. We loaded our belongings into the boat then headed north through the fjord, seeing some more icebergs on the way.

After a quick stop at Billy’s camp to pick up some more tourists, we navigated through some more icebergs and islands to arrive at Qikiqtarjuaq.

We landed at the dock, walked to the only hotel in town, and checked in. It was after hours, but the staff still generously made dinner for us. After a week of freeze-dried meals, the burgers and poutine were excellent. We slept well that day.

Qikiqtarjuaq

Qikiqtarjuaq is a small town (500 people) located on Broughton Island, 80km from the north trailhead and 500km across the Davis Strait from Greenland. Inuit have lived off the land for centuries in this area, but the site of Qik developed as a community in the 1950s when a Distant Early Warning (DEW) line station was established. The name means "big island" in Inuktitut (The Canadian Encyclopedia).

The five of us spent the next morning walking around town, exploring the beach and hill and meeting the locals. We had to deregister at the Parks Canada office to let them know we’d arrived safely. Dave and Eli had to leave that day, but Dad, Neil, and I had an extra day in town.

On a distant peak, the surreal-looking dome of the DEW line station can be seen. This is very close to the highpoint of the island, and I was interested in visiting it. I mentioned this plan to Sebastien and Billy on the boat and they were very concerned! Unlike on the Akshayuk Pass, polar bears are very common on the shores of Broughton Island, and it isn’t safe to stray too far from town.

We abandoned our peakbagging plan, deciding instead to find a boat tour. Billy was unavailable, and no one else offered organized boat tours, but the hotel manager offered to ask around and find someone for an unofficial tour. She eventually found a local named Stanley who could take us around the island.

Our boat went counterclockwise, past an abandoned whaling station and the cliffs of neighbouring islands, then out onto the Davis Strait, with nothing separating us from Greenland.

On a flat bench below the highpoint, we saw a mother polar bear and her cubs surveying their territory. We left quickly...

As we approached town, Stanley noticed something on the shore and spent some time trying to approach it. It was a barrel! This generated much more of a reaction than the polar bears.

The next day, we began our long journey home. The skies over Qikiqtarjuaq were clear as we flew out of town, giving us an excellent view of the icebergs in the fjord and the icecap covering the peaks. As we approached the pass, clouds engulfed our route, but I kept track of the map to see where we’d gone.

Dad, Neil, and I spent another day in Iqaluit: I had another shawarma meal, sampled a cloudberry sour at Nunavut’s only brewery, and visited the Nunatta Sunakkutaangit Museum (a small museum, but they have an extensive collection of articles on Nunavut’s culture, history, and geology, an excellent way to kill time). We went our separate ways, with Dad flying to work elsewhere, Neil heading home to Vancouver, and myself flying to Montreal to visit friends and relatives. It was time to say goodbye to the North.

Words cannot describe how incredible this trip was. I will remember this unique place that very few Canadians get to visit, with its stunning scenery and rich, distinctive culture. I’m very grateful to my dad for organizing this trip and to Neil, Dave, and Eli for joining us. I hope I can return to Nunavut someday.

Logistics

Here are some logistical concerns that might be helpful to future adventurers. Note that all of these are my opinions after only one trip to the area. Cross-reference these with other sources.

Navigation and routefinding:

The best map we had was Chrismar Mapping Service’s map, which covers the entire pass (https://chrismar.com/products/auyuittuq-national-park-akshayuk-pass). On top of the map itself, it includes logistics, park information, and historical, natural, and cultural information about the area. It was absolutely invaluable. In contrast, online mapping services (such as Gaia and Caltopo) are not very detailed or reliable at these latitudes, and should not be relied on.

In good weather, routefinding was less difficult than we expected - there’s only one large valley, and if you’re climbing a mountain or traversing a glacier, something is wrong.

Fuel:

Despite what you might read elsewhere, isobutane and propane fuel canisters, used by most camping stoves (Jetboil, etc) are not available in Pangnirtung, and this is probably also the case in Qikiqtarjuaq. The only fuel available in Pangirtung is naphtha (white gas), which requires a specialized stove. It would be more economical to buy a white gas stove at home than to expensively ship other fuel to the Arctic. Naphtha can be bought at the Northern Store in Pangnirtung, and sometimes departing hikers leave half-used canisters at the hotel or B&B.

Direction:

Parks Canada recommends traveling from north to south. The boat ride from Qikiqtarjuaq to the northern trailhead is much longer than the ride from Pangnirtung to the southern trailhead (88km vs. 28km) and passes through rougher water, so delays are more frequent at that end. As you’ll learn in the polar bear safety video, polar bears are more common near coastlines, and are more commonly seen on the northern coast, and on Broughton Island around Qikiqtarjuaq. (Edit: we were told that no polar bear has been seen on the actual trail for many years, but that changed a few months after our trip when a polar bear injured a skier at Summit Lake, in the middle of the traverse). We traveled from south to north due to one group member’s work schedule and had no problems.

Timing:

Parks Canada recommends taking 8 to 12 days for a full thru-hike (about 8.2 to 12.25 km/day). We managed it in 5.5 days at a reasonable pace, although this was in the summer of what seems to have been a dry year. Several logbook entries mentioned delays of several hours or days due to high water levels at creek crossings, but we luckily avoided this. It’s also wise to leave extra days at either end of the trip in case of delayed flights or boats, a common occurrence in the Arctic.

Most of the route involved navigating a faint trail, or no trail at all. The surface is mostly spongy bogs and tussocks, slowing down hikers with little experience in off-trail travel. However, if you're used to off-trail navigation in coastal BC, then even the tussocks are quite manageable. I think 6-8 days between the two trailheads would be a reasonable estimate for parties with experience in hiking and off-trail navigation, with 5-7 days spent actually hiking, one or two on-trail buffer days to account for delays and side trips, and some extra days in town on either end of the 6-8 days to account for flight delays.

There are reports that the route has been completed in 18, 23, or 25.5 hours (Fastest Known Time). https://fastestknowntime.com/route/akshayuk-pass-nu-canada Peter Kilabuk, the boat operator at Pangnirtung, has completed it in three days but I’m not sure if that was by foot or snowmobile.

Creek Crossings:

There are many creek and river crossings along the route, none of which have bridges. I found the Highway Glacier outflow and the subsequent Owl River crossing to be the most difficult. Half Hour, Turner, and Norman are other creeks that have given previous groups trouble. As shown by hut logbooks, many groups have had to wait for hours or days for waters to recede. We were there in one of the drier months of a dry year and didn’t have to do that, although the Owl River still gave us trouble.

The streams are glacier fed (cold!), and are at their lowest in the very early morning, before incoming solar radiation starts melting the glaciers. Many 4 a.m. crossings are mentioned in logbooks.

I brought water shoes for the crossings, which allowed my regular hiking shoes to stay dry for almost all of the trip. I thought they were quite helpful. Other groups will go further, bringing neoprene booties. The rest of our group just walked across the creek crossings in trail runners, which mostly dried out quickly. It depends on your preferred style of creek crossing.

Side Trips:

Little information exists online about climbing the mountains along the pass. Some of the unnamed peaks in the northern half of the pass, less steep than Thor and Asgard, seemed like they could be accessible without technical climbing. Additionally, it seemed possible to scramble up Mount Battle (on the south shore of Glacier Lake) from its eastern side, but we didn’t have time to explore. Some groups will take side trips to the base of Mount Asgard (see https://www.ronperrier.net/2020/01/05/akshuyak-pass-auyuittuq-national-park/ for directions). Climbers and groups with glacier travel gear have many more options.

Polar Bears:

Everyone hiking in Auyuittuq National Park has to watch a terrifying polar bear safety video (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kLWG_73v948). Polar bears are most commonly found along coastlines. We saw no signs of polar bears during the traverse, and we were told that they had not been seen along the trail in thirty years. (Edit: That changed a few months after our trip when a polar bear injured a skier at Summit Lake, in the middle of the traverse). As we found out later, bears are far more common around Qikiqtarjuaq…

Member discussion