Great Divide Trail Section D

Field -> Saskatchewan River Crossing

August 4-9, 2025

106km

GDTA Link: https://greatdividetrail.com/go-hiking/section-hiking/section-d/

Side trips: Mount Field

My GDT experience began on section D. This used to be considered the ‘black sheep’ of the GDT, with early trip reports mentioning extensive bushwhacking and endless deadfall. Recent improvements have really improved things, but it still had some of the most difficult sections.

Most hikers will take the Kiwetinok alternate, which follows the popular Iceline trail, then completely changes into a rough route that climbs to a pass. Past the Iceline trail, the route drops 500 metres into a valley through the worst bushwhack I encountered on the GDT, then climbs almost 400 metres out of that same valley in the steepest section of the GDT (there are cliffs preventing a more direct route). The rest of the route follows a series of rivers to their sources, including the historic Howse Pass, then follows the splendid Howse Floodplain to civilization. This section is not traveled often: I only saw one other person between the Iceline trail and Saskatchewan Crossing, which wouldn’t happen again until the much more remote section G.

The adventure started with a cheap evening flight to Calgary. The next bus to Field wouldn't leave until early the next morning, so I spent the night in a quiet place in the airport. Out of all the campsites on the GDT, this was one of the worst. Its proximity to clean running water, vending machines, and restaurants were redeeming qualities.

The next morning, I woke up early, caught a bus, and headed west. It was striking to see the wall of mountains rise out of nowhere from the plains. Since I wasn’t doing section C, I wouldn’t be hiking anywhere near these mountains. After some time spent admiring the views on the Icefields Parkway I arrived in Field, where I spent some more time buying the required permits and sorting out last minute university-related issues. I then headed across the highway to begin the hike.

The Burgess Pass trail switchbacks upwards for almost one vertical kilometre. This was quite the grind, especially with 12 days’ worth of food in my pack! I was still recovering from the recent tree planting season, and many muscles were quite sore. It took much longer than expected to make it to the pass. I eventually reached the pass, where I was treated to the first of many stunning panoramas.

From here the trail wrapped around the western flanks of Wapta Mountain, a jagged ridge resembling the prow of a ship. I wanted a break from the heavy pack, so I hid it and took a short side trip to Mount Field. A short scree ascent led me to a cliff band, which presented a short class 2 scramble. I spent some time on the summit, admiring the many mountains including Mt. Assiniboine in the distance. Almost fourteen hundred metres below me, cars and trains passed through the valley, so small as to seem like toys. Eventually storm clouds appeared on the horizon, my cue to leave immediately.

I returned to the main GDT and continued heading north. The trail passes the Burgess Shale, one of the most important paleontological sites in the world. The formation preserves the fossilized remnants of a 506-million-year-old shallow sea, providing insights into the origins of many modern animal groups. Parks Canada has a map showing where the cool stuff is. However, entry is prohibited without a guide, and the fines are very high.

The storm clouds reached me and light rain began to fall. It stopped quickly, but I was already soaked; a recurring theme here. My boots wouldn’t fully dry until Jasper, which caused problems later…

I reached the Yoho Lake campsite with plenty of time to spare until sunset. This ended up being the most crowded campsite of the trip by far, with all campsites full, including several families with young children. The peaceful wilderness experience I’d expected would wait until tomorrow.

The next day would mostly be on the popular Iceline trail. After a few kilometres of solitude past Yoho Lake, it was surprising to see hundreds of day hikers, many of whom were a bit surprised to see someone with such a massive pack!

For basically all of the GDT’s stretch of the Iceline, Takkakaw Falls can be seen across the valley. At 373 metres, it is the tallest in the Canadian Rockies, and its roar can be heard from many kilometres away. On my side of the valley, the trail traversed below glaciers and around glacial streams.

The party ends when the trail leaves the Iceline, climbing to the rarely visited Kiwetinok Pass. More storm clouds appeared and the temperature dropped. It began to rain.

On the way I met Alex, an Australian who was thru-hiking the trail. It was nice to meet a thru-hiker so soon. He ended up being one of only four thru-hikers I would meet on the whole journey. He was wisely heading back to the hut, avoiding the worsening weather. In hindsight this would have been a good decision.

Only 7.8 kilometres of trail separate Kiwetinok Pass from the main GDT in the Amiskwi. However, the sheer cliffs on the south face of Kiwetinok Peak block the most direct route. To bypass these cliffs, the trail descends almost 500 vertical metres into the Kiwetinok River valley along talus slopes. The trail was indistinct here, requiring extensive bushwhacking through chest-high willow bushes, soaking everything. From there, the route painstakingly regains 400 of these vertical metres, climbing northwards to “Kiwetinok Gap”. The first kilometre of this section is the steepest of the GDT. The rest of it is above treeline, and the wind and rain were fierce. At the gap, the trail can finally begin its long, long descent to the Amiskwi, where I found a usable campsite on a former logging road. In one day I’d seen some absolutely incredible scenery interrupted by awful weather. This set the tone for most of the rest of the trip.

I was finally on the main GDT route, which followed the Amiskwi and Blaeberry rivers to their sources. At one point I passed a burned cutblock, bringing back memories from the recent treeplanting season.

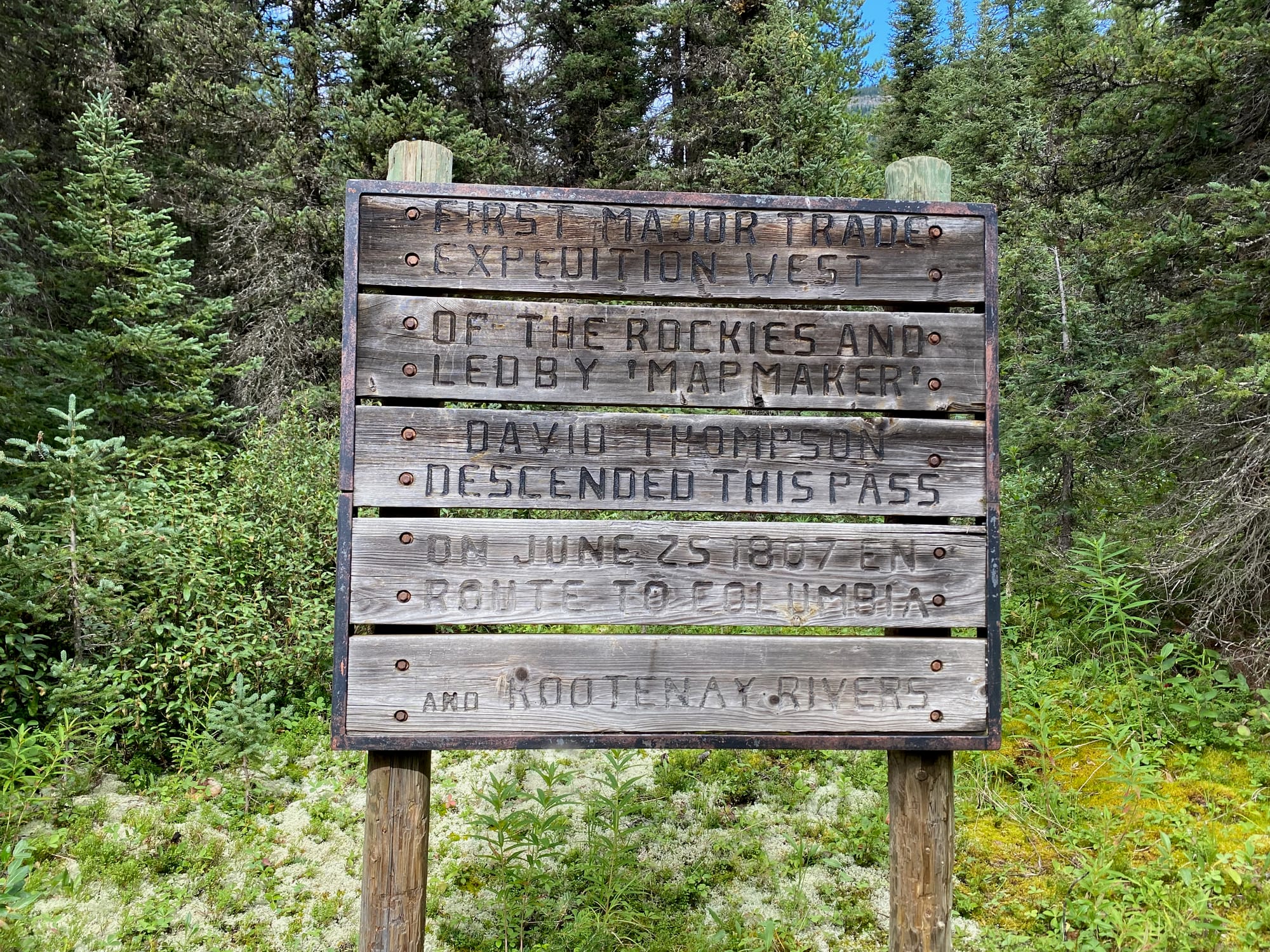

The Blaeberry River reaches its source at Howse Pass. At 1530 metres, this is one of the lowest passes crossing the Continental Divide in this area, and as such it was very important for trading in the pre-colonial and fur trade eras. Somehow it has remained undeveloped, thankfully. It might see fewer visitors now than it did two hundred years ago. In 1807, David Thompson crossed the Rocky Mountains through this pass on his way to survey the Columbia River, the first major trade expedition west of the Rockies. The pass’s namesake, Joseph Howse, crossed it in 1809. After 1810, the Pikani blocked this pass, forcing fur traders to use alternate routes. Several plaques, signs, and boundary posts mark the site. [Source: Parks Canada]

Next up was the Howse Floodplain, easily the highlight of section D. I wandered along the banks of the glacial Howse River through meadows dotted with wildflowers. Jagged peaks rose on either side of the valley. The wide, open plain was quite a contrast to the many forested stretches of the past week. Each step revealed more of this sublime valley.

At times the Howse River cut close to the valley wall, forcing me to take the overgrown trail through the forest. Some of it is maintained, but the extremely high water levels this year forced me to take a few sections that aren’t maintained. Lots of frustrating deadfall had to be negotiated here, and I ripped my pack at one point. Luckily, I was usually able to return to the wide-open, glorious floodplain within a kilometre or two.

As the river curves around Mount Sarbach, a side trail leads to one of the nicest campsites I’ve ever seen. A peninsula cuts into the floodplain, surrounded by mountains.

The trail leaves the floodplain, eventually reaching the highway at Mistaya Canyon. I hadn’t seen another person in two days, and now I was in the middle of a busy tourist attraction. It was quite jarring!

Some road walking brought me to The Crossing resort. This wasn’t too bad as far as road walking goes, with excellent views of the peaks marking the start of the next section. Along the way, I was stopped by a ranger who wanted to make sure I had all my permits. Luckily, everything was in order.

I spent a long time at The Crossing, enjoying an expensive meal (you have to cook the burger yourself, for some reason, but there is an all-you-can-at soup and salad bar, which I hit pretty hard), letting my family and friends know I was alive, and buying some supplies. After the openness and solitude of the Howse Floodplain, it felt very claustrophobic to be in a crowded building with so many other people. This, after being on the trail for less than a week…

Section E beckoned.

Member discussion